I’ve had a few Chinese teachers since I first arrived in China back in 2014 and just about all of them have been good for what I was looking for at the time. Some I studied with for only a few months, others I stayed with for longer. My current Chinese teacher, whom I meet once a week on Mondays, was recommended to me by a colleague and a fellow Chinese student. And I’m glad my colleague did because this Chinese teacher even teaches me how to teach.

“She is the kind of teacher we are supposed to be,” I often tell my colleagues about my current Chinese teacher. Since commencing lessons with her in the middle of this year I have subsequently recommended her to a few other colleagues who’ve all had positive things to say about her.

So, what’s so good about this teacher?

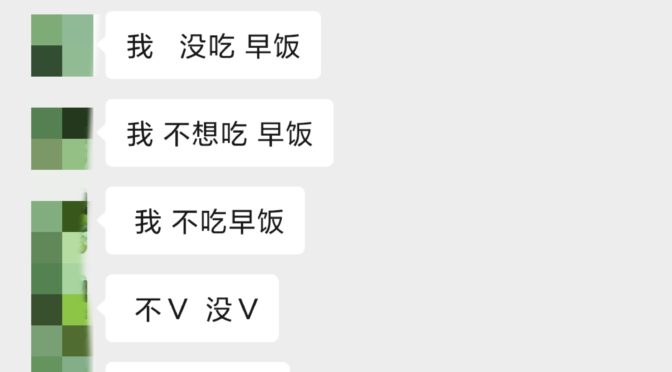

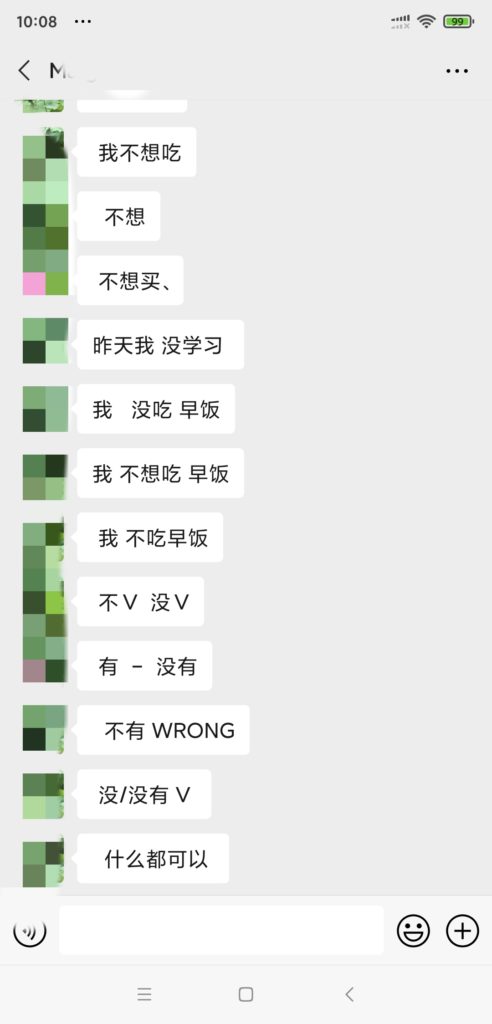

For one, she makes things simple and then builds it up, but in an indirect fashion, not a sly warm up game or something that you’ll often find in an ESL class. Instead, even with a simple conversation, she’ll then pick out one or two sentences and write them out for me to look at. She’ll then ask if these are correct. Of course they’re wrong but she wants to know if I can now see what the error(s) would be. Sometimes I can but most of the time I can’t, mainly because it’s a grammar issue. I still speak Chinese with English grammar structures, and this method, although it still gets the point across, would sound odd to a natural Chinese-speaking person.

I should add that all of my classes are taught online and, unlike other teachers, is only a phone call. I have no idea what my Chinese teacher looks like but I have in mind that she looks similar to one of my previous teachers who was married and also a very good teacher, but I have nothing to back this up.

This is one other characteristic about my teacher that I do appreciate: it’s all business. I don’t know much about her personal life (I don’t think she’s married but I do know she doesn’t have kids) and she doesn’t volunteer very much information either. I respect that. Instead, she focuses on my language and my communication abilities.

Is it odd just having a phone call? Not at all for the simple reason that I can hear her typing furiously away the sentences she wants to demonstrate. This is probably one of the best qualities of the class: her ability to pull out a sentence, either my own or from the textbook, and pull apart each segment.

So, what have I learned so far?

The basic structure for a Chinese sentence is as follows:

Subject + verb + object + whatever else

Seems simple enough.

The problem is that it’s a bit more complicated than that and this is where I get flipped around. The structure is more like:

Time stamp + subject + verb (part 1) + object + verb (part 2) + whatever else

What are these “parts” to the verbs?

Some Chinese verbs, called conditional ____, “hug”, “embrace”, or otherwise surround their object.

For example, to say “I came back to Beijing, is

“我回北京来” wherein

- 我 (wo) is the subject (“I”),

- 回 (hui) is part one of the verb (to come back / return),

- 北京 (Beijing) is the object, and

- 来 (lai) is the second part of the verb (to proceed or enter).

Seems easy enough when writing it out because you can correct it, but in spoken discourse, by the time you realize your mistake, the point has already been made and people have registered that your grammar is bad, but they will respect your effort for the response.

So that’s been one of my big issues with Chinese grammar thus far.

The other issues stem, again, from my reliance on English grammar. Another example would be the idea of a time stamp:

In English we’d say something like this:

I went to the store yesterday.

In Chinese, it’s:

昨天我去了超市。

OR

昨天我去超市了。

Wherein 昨天 (zuotian, yesterday) is placed before the event actually happened. It’s the same with other times, eg, “in the afternoon”, “at eight o’clock”, etc. Generally the time stamp goes right at the beginning of the sentence and is then followed by the subject + verb + object structure mentioned above.

You’ll also notice in that sentence the particle, 了 (le), which signifies a change of situation, can be placed either right after its verb (which, in this sentence is 去, qu, “to go”) but can also be placed after its object (in this sentence it’s 超市, chao shi, “market”). Recognizing this while reading is one thing, but being able to think and speak these grammatical structures become a little bit more difficult if you’re not used to it.

How to fix these problems?

Suffice it to say, taking more classes won’t necessarily help with my speaking. It will help a little bit but it wouldn’t be the best solution, especially since it would cost more money. Speaking with other people doesn’t necessarily help either since a lot of speaking a language comes down to understanding what is being said and what you need to say in response, ie, listening and speaking, which, when put another way, comes down to vocabulary. And that is what I have been working on for the last year or so.

So, having worked on vocabulary (currently making my way through the HSK 5 vocabulary list) and practiced my writing skills in an effort to help with my reading skills which help support a build up vocabulary, I now need to work on actually saying the words I know and, moreover, understanding when they are said to me.

Sounds simple enough? Sounds like you need to practice more.

Keep in mind Mandarin Chinese is a tonal language yet and uses characters to represent a sound. Even with pinyin (writing Chinese words with the Latin alphabet), two words can have the same tone but have different characters and thus different meanings. This means the pronunciation could be the same but the meanings would be different. This would be an issue if I were reading something or, if my abilities allowed, I wanted to write something.

How am I addressing this issue?

I’m doing two more things now that I wasn’t doing before:

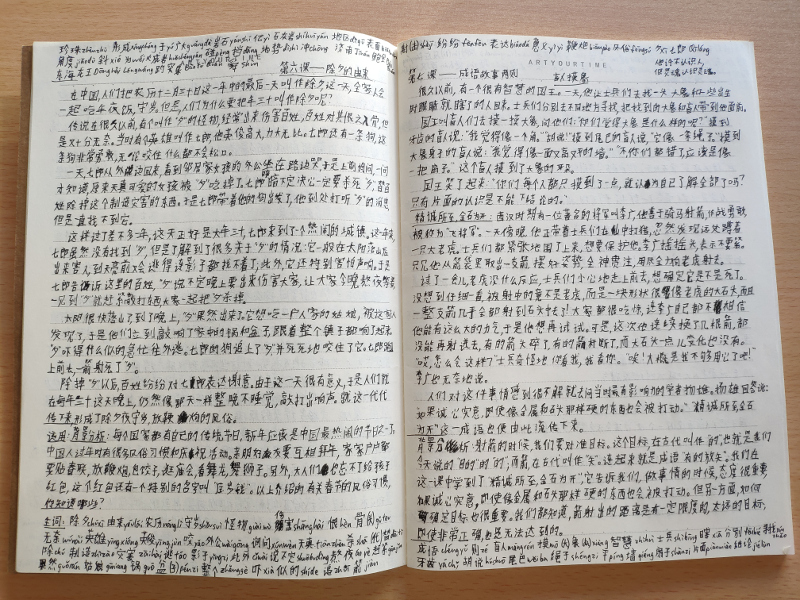

First, I’m writing out entire sentences and paragraphs, copied from various sources ranging from my textbooks to newspapers.

Second, I’m reading out loud for 30-60 minutes per day, and focusing on reading sources with pinyin (such as my graded readers) or texts that are easy enough for me to read the Chinese characters themselves (such as my textbooks).

And so that’s the goal right now: speak more every day to get my mouth muscles used to pronouncing the Chinese sounds and write full sentences in an effort to improve my grammar and visualization of the Chinese characters.

Overall, I have seen some improvement in my language abilities and it’s hard to believe that I’ve been at this for nearly three years. I still feel as if I’m a long way’s away from where I want to be but, as I make my way through the HSK 5 books, I notice that some things are getting easier where they used to be difficult.

The progress is there though it seems to go slow sometimes.

***One last note, one of my goals was to finish the HSK 5 books by the end of this year. As the end of November draws near I’m finding I’m sorely behind on that goal. I’m not overly concerned since I have been redirecting my efforts in other areas, notably the writing. I have, however, been rather lazy with my studies and not as driven as before. One reason is the restart of work and another is that there have been other things I’ve had to get done which prevent me from sitting down to work through the textbook. Going forward I will break down my attack on my textbook into smaller chunks instead of trying to do an hour-long slog through grammar exercises.

Hey! Steve! When will we be able to hear you speak?

🙂