I’ve been back in Beijing for about six months now and have finally gotten settled into my new apartment on the other side of town. Whereas before I was in the student district, now I’m very much in the expat district. This isn’t a problem insofar as food options is concerned, but it is a bit more of a concern for the development of my Chinese skills. However, I’m refocusing my Chinese studies this time round in that, in addition to my daily speaking practice, I’m trying to do more reading as well.

You’ll recall a few years ago that I posted about my first attempt at reading Chinese, citing the words of some German PhD holder “When I wanted to learn English, I just picked up the newspaper and started reading.” Well, Chinese isn’t so easy… or is it?

You see, unlike three years ago when I first arrived to China, I have a bit more experience behind me and, more importantly, I have a working knowledge from which I base further development of my language skills. It also helps that many of my current colleagues are either fluent or at least knowledgeable in the Chinese language so I can seek some sort of inspiration from them when my lags.

But I didn’t want to just sit down and read dry textbooks or see a teacher once a week and have her (it’s usually a female) talk at me while grinning through my terrible Chinese. Furthermore, I simply don’t have the time since I’m on the move quite a bit with this new job.

And so I got thinking about that PhD holder’s words and then another thought popped into my mind:

What would Jack Bauer do?

If you haven’t watched the TV series 24 then I highly suggest you get on that right quick. Although getting dated in terms of its technology day by day, the story, and the main character, Jack Bauer, were the modern Chuck Norris. Anyway, those of you who have watched the TV series might be familiar with the scene in which some Russian thugs confront Bauer as he is doing something he’s not supposed to be doing. However, instead of cringing away under a hail of gunfire, he did what any other worldly man would do:

He spoke to them in their language.

You see, Jack Bauer didn’t learn Russian in that episode. Russian learned Jack Bauer.

Jack Bauer wouldn’t sit down with some school boy textbooks nor would he sit down with a teacher unless he was… interrogating her. No no, the textbooks would chase him as he sped through the pages of a modern novel or grammar book (you know, just to get the arrangement of words correct) and instead of going to see a teacher, a teacher would go to see him. That teacher would be called the school of real life.

And so it is with the same approach that I will attack my new focus of learning Chinese.

So what am I focusing on this time?

I want to build up my reading of Chinese characters so I also use a couple of websites that are dedicated to learning Chinese but don’t just give you the answer. They include www.slow-chinese.com and www.learningchinesethroughstories.com.

Of the two, Slow Chinese is a bit better because they have consistent sound quality whereas Learning Chinese Through Stories has variable audio quality, which is an important factor when you’re trying to listen to these podcasts on a subway. (The subway wheels make screeching sounds that makes listening to talking podcasts a bit difficult.) There is also Chinese Pod, which has been recommended, but their videos take longer to download and, moreover, I’ve had problems logging in to my account so I can’t always access the premium content they promise.

The great thing about the above podcasts is that they offer both the text and an audio recording of the text so I can follow along, which is good for learning the different characters. Luckily, having been in China for a few years, I can follow along pretty easily, though I’ll admit I still don’t understand everything.

The next thing I’ve tried to incorporate into my travel life is reading Chinese novels. Why Chinese novels? Well, much like in English, depending on the type of books you’re interested in, reading novels is a great way to expand your vocabulary as it helps you literally visualize what the words look like as you sound them out. I’ve always encouraged my students to read novels in English, especially the ones they’ve already read in their own language.

Now, Chinese is a little bit more difficult in that the characters don’t lend themselves to being “figured out” by way of sounding them out. Nor can you “deconstruct” a Chinese character in an effort to understand its pronunciation (though you could make a guess at its definition). In effect, reading Chinese is more like a memorization game of “Hey, I know that character” and then piecing those characters together to form a word that you can then identify as having a certain meaning. All that is to say: it’s like reading pictures and figuring out how they all work together.

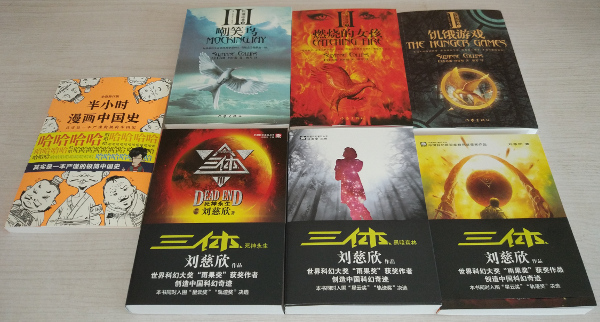

But these are becoming mere excuses at this point. Three years in this country and at some point you just have to get past it. And that’s what I’m trying to do. You might be interested in what I’m trying to read. Here’s a pic:

The first set of books I bought is 三体 San ti, The Three Body Problem, a trilogy of sci-fi books written by Chinese author Liu Cixin. Why this trilogy? I had heard about this trilogy last year while I was in Canada and found that the Winnipeg Library actually has a copy of the first book in English, so I read that. The basics of the story are that there is this guy who keeps playing a video game (a very Chinese thing to do) that keeps dying on him. As the novel progresses, we see that the video game has actually been set up by an alien race in an effort to save humanity from its ways. The story is interesting enough and the Chinese is supposed to be easy enough that I should be able to make my way through it. However, as it stands, it might still be above my level.

(Oh, btw, science fiction seems to be the way that modern Chinese writers critique the goings on of their authorities. So, if you want to read or hear what “the people” have to say about their powers that be, pick up some Chinese science fiction. That is, of course, in addition to a book or two on Chinese history. Or Wikipedia.)

Now, if you’re wondering if that’s The Hunger Games you see, you’d be correct. I bought the whole trilogy for under $20 CAD since I’ve been told it’s also an easy read. So I’ll add that to my “to read” list this year.

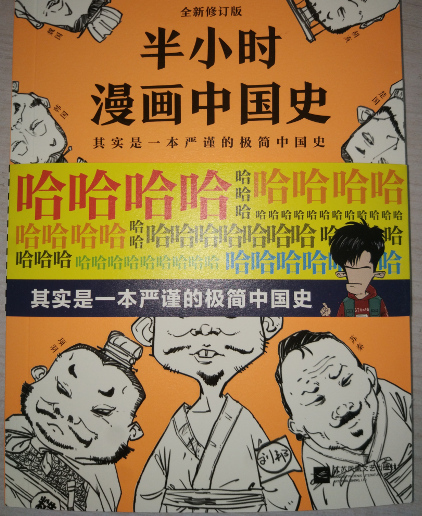

The one on the far left, the orange-covered book, however, is the one that I think I might tackle first. The book caught my eye at one of the airport bookstores when I asked the retail lady if she knew of any easy Chinese books to read, like the Little Prince (小王子 Xiao Wang Zi in Chinese). She looked and pointed to these comic-like books of Chinese and this one stood out among the others. I settled on this one:

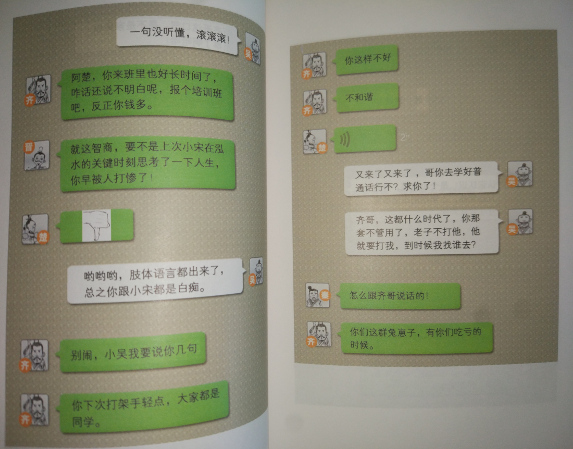

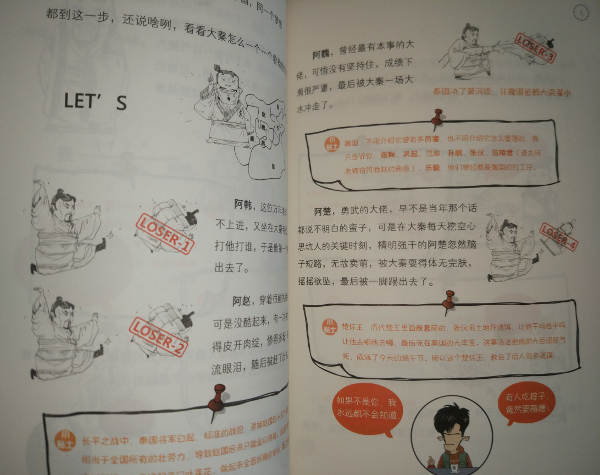

Apparently it’s about Chinese history (from the Chinese perspective) but the interesting thing about this book was the rather cheeky way it presented that history. Here’s what the inside looked like:

So, instead of just pure text, there are caricatures of people from throughout Chinese history in various forms of expression and reaction to the historical narrative. All in all, a rather cute way of learning Chinese history, and probably just about my level.

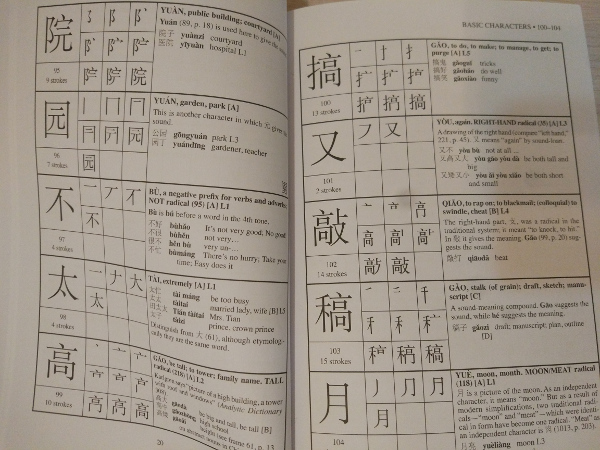

Finally, the last thing I’m trying to do is work my way through a reference book that I bought a couple of years back. Titled Reading and Writing Chinese: A Comprehensive Guide to The Chinese Writing System, it’s about as exciting as it sounds… unless you’re actually studying Chinese and then it becomes a pretty good guide book through the language.

How am I using this book?

This is not a book that instructs you through a maze of grammar or silly mnemonic devices. Instead, by sorting the 1700+ characters into three or four “lists”, the book enables you to break down the characters into manageable chunks. The first list, known as “List A”, comprises some 800 characters that are the most common to be found in the Chinese language. “List B” is another 804 and “List C” contains another 604 characters. Yes, that’s lots of characters. But they do build on each other and, since I’m living in China at the moment, it is practical to learn these characters as I do see many of them every day.

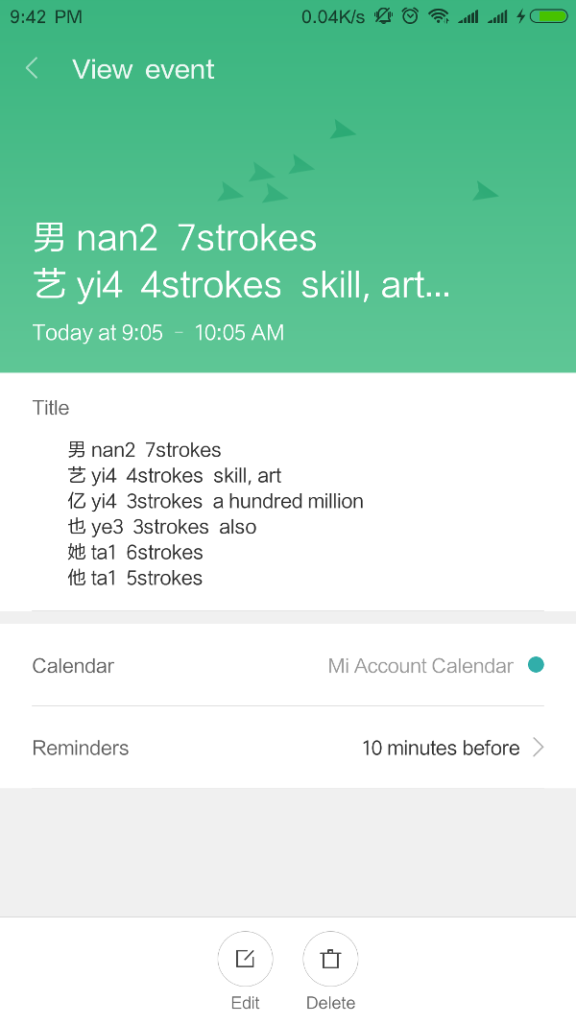

I’m writing up lists of seven characters per day (the recommended dosage) and inputting them into my calendar app on my phone. That way, every day, at about 730 am, when I’m on the subway, taxi or van, I get a notification for seven new characters that I can think about throughout the day. And that’s all I focus on. Some of them I know, others are brand new.

And so that is where I stand in regard to my learning Chinese. It’s not great but it does seem functional. I have no illusions of working for a Chinese company wherein I’d need to be fluent, but that scene of Mr. Bauer Russian-ing it up kinda has me thinking I could at least get to that point.

All that being said and done, I guess it’s kinda true: if you want to learn a language, start reading!