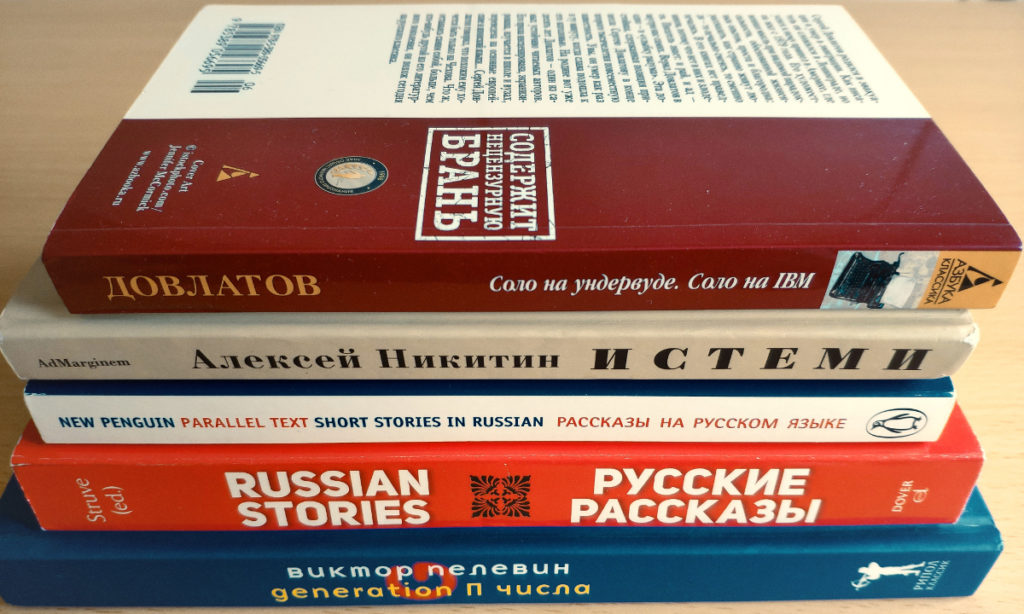

These books have been sitting in my apartment since I moved in and I’ve hardly had time to look at them. Actually, it wasn’t the time, it was the ability to look at them and spend the time to read and gain something from them. I bought these books when I was traversing through Russia along the Trans-Mongolian Railway (so-called because it goes through Mongolia rather than just through Russia) with the idea that I would take up my Russian studies once I returned to China after the trip was over.

Well, if you’ve been following along for a while, you’ll know that my plans in 2017 were interrupted with the news of my Father’s passing. Subsequent events disabled me from returning to China in a prompt manner and, as a result, put off any time and energy to learn Russian.

Fast forward to 2021 and now I have a bit more time, energy, money and desire to work my way through yet another language. This may leave you wondering, why Russian?

Prior to my train trip across Mongolia and Russia, I wrote a post about my change in language studies just prior to departing Beijing.

- Giving up on Chinese… for Russian? – https://www.stevensirski.com/giving-up-on-chinese-for-russian/

In that post I went through a few reasons why I chose to pick up Russian in the first place. Nothing much has changed since then. The language is “global” in the sense that quite a few people speak it not just in Russia, be them Ukrainian, Mongolian, or even from the Middle East. Next, since I studied Ukrainian as a kid the basics of the language are there and the culture is familiar. Further, I’ve spent time in Kharkov, Ukraine, which is a very Russified city. Finally, then as now, it’s a nice break from studying Chinese.

The last point is probably the biggest reason I’ve decided to pursue the language and hire a Russian teacher. Although I could go through my Russian textbook (again) and then read through the materials I have, I have found that, in all of my language learning, teachers remain one of the best deadlines to have. That is to say, every class is like a mini-test that you have to prepare for. And if you do your homework and prepare for class, this test is a lot easier. If you don’t, well, it’s your money and your time, what do you think it’s worth?

Similar to 2016 when I first approached Russian, once I picked up the textbook and started reading the language I couldn’t help but feel an immediate sense of relief. This relief stems from the fact that I still find myself struggling through authentic texts in Chinese. Even if the text is “easy” I still may not be sure of a character or how it should be translated, to say nothing of the characters I don’t actually know.

But reading the Cyrillic alphabet is simply much easier than reading Chinese given the fact that I can parse each part of a word. Sure, there are some long words in Russian that require me to slow down and pronounce each part individually. But, for the most part, however, it’s a lot easier to read.

I feel the need to mention that I am not giving up on Chinese and I am not forsaking my Ukrainian heritage.

I am continuing with my Chinese studies and will continue to do so as long as I am in the country. As I write this article I am preparing to write the HSK 4 test in May which will gauge how many characters, words and grammatical structures I currently know. I should know about 1200 characters and words and some number of grammatical structures (I can’t remember the number exactly but there are a few standard structures people who pass this test will know) and so this test will help me gauge my progress so far.

Further to the point, my Chinese language skills are far better than they were back in 2016 and, thanks largely to my efforts over the last three years, I’ve made great strides in the boring parts of the language, particularly writing and memorizing the core words and characters. Although I still need to focus on some characters I don’t know, many of the words at this level are made up of characters I already know. All this means is that the language isn’t as much of a struggle as it was back in 2016. In other words, I can “breathe” a little in my Chinese studies.

Now, what about that Ukrainian heritage?

I’ve talked to a few people since I first picked up Russian a few years ago and they sort of made it clear, though they never explicitly said so, that Russian is just another language to know and that being able to speak it in combination with another language (such as Chinese) isn’t a bad thing at all.

I refer to my own podcast for these conversations. Episode 19 with Liubov Lomonosova, who hails from Kyiv, Ukraine but now lives in the USA with her husband, and Episode 20 with Anna Bass who is originally from Moscow, Russia, but now lives in New York.

In my conversation with Liubov I mentioned that Ukrainians have always acted as translators both linguistically and culturally between Russia to the East and Poland and Europe to the West. She corrected me and said it wasn’t so much their choosing so much as their necessity given their placement between the two geographies. That is to say, the Ukrainian education system incorporates both Russian and Polish into their teaching so that the result is a Ukrainian will often have knowledge of all three languages rather than just one or the other. Oh, and add English on top of that for a total of four languages a typical Ukrainian person in a city would have knowledge of.

Then there was the story of Anna’s experience of coming to China to study Chinese and subsequently being drafted into a film production as a translator between Chinese, Russian and English. She pointed out that, at that time, not a lot of people spoke Chinese very well. Nowadays, however, lots of people are studying or know Chinese so it’s not so difficult to communicate. To say nothing about the ubiquity of the English language.

And, just to make the point clearer, both of these episodes were done in English with people who were speaking English as a second language. Time to step up, I guess?

So, is learning some sort of transgression against my ancestors and heritage? No, not really. I mean, if you hold it against me that I’ve left Canada to work in other countries, you may have a point. But then noting that I teach ESL kind of puts the argument back into the “not a transgression” territory. I’ll let the historians debate that.

So what’s the goal?

Here’s where things get funny at least in the sense of, “You want to do… what?”

Fluency and ability to translate between the three languages of Russian, Chinese and English.

WTF?

This is not as odd as it sounds if you consider that there are Russians who’ve come to China to study Chinese but are also able to communicate in English (I have a colleague who is able to do just that). Further, that there are Chinese students who, after being forced to learn at least some English in their school life, also have the choice to learn Russian or Japanese instead, and some go on to further their Russian studies at university. So, in some sense, I’m playing catch up in this game. The problem for me, of course, is that I’ve picked two languages that are considered some of the hardest to learn for native English speakers.

I won’t even touch on the criticism of an aging body and mind as there is enough evidence to suggest that learning a language is more about re-training your brain rather than how old you are. Pronunciation as you age, that’s almost a different story but, as far as I can tell, has more to deal with the muscles of the mouth and the ability to retrain those to pronounce the necessary phonemes, or sound parts.

When my teacher asked me what my goal was I told her that it was to be able to take the C2 exam in Russian by this time next year. After a bit of practice language, she commented that I knew more than the basics but that, obviously, my grammar and pronunciation were not very good. She also never said it would be possible or a good goal to have, but I don’t care, that’s the level I’m shooting for right now.

So, by March or April of 2022, I want to be able to make my way through the C2 exam in Russian.

For those of you who aren’t familiar with the C2 exam, the letter belongs to a framework of language grading, known as the Common European Framework for Reference of Languages. There are six levels, ranging from A-levels (easiest) to C-levels (hardest) with the order being A2-A1-B2-B1-C2-C1. The level of C1 would be considered on par with a “native” or a “naturalized” speaker of the language (but dealing with all language skills, not just speaking). So, my goal of C2 is just below that of a native speaker.

What level am I right now?

I would like to think I’m sitting at a B2 or B1 level but the reality is probably a bit lower than that. Reading the back cover of my Russian textbook (by Nicholas J. Brown), the book only aims to take learners up to the top of the A-levels. So, if I struggle with that book then that means I’m probably somewhere near the transition from A1 to B2.

So, with that, I’ve now started blocking off Thursdays and Fridays as my “Russian Days”, starting with listening to the radio in Russian, conjugating verbs and declining nouns while reading through grammar explanations and retyping short stories on my cell phone, culminating in my language class placed conveniently on Friday evening.

With that, they say 加油! in Chinese, but in Russian they say давай!

Давай!