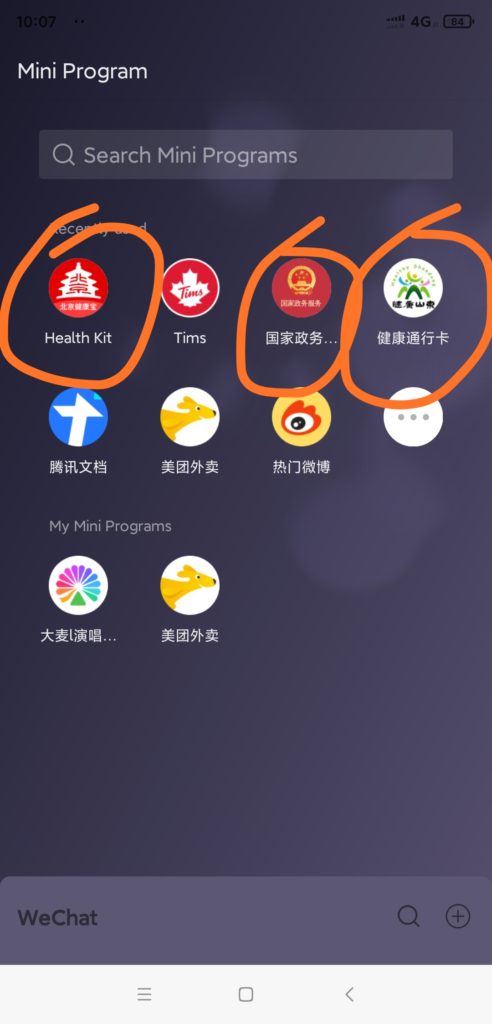

We’re finally back on the road for work, but the experience is a touch more complicated in that we now have to download, and register, a slew of new APPs, most of which are primarily in Chinese.

What are these APPs?

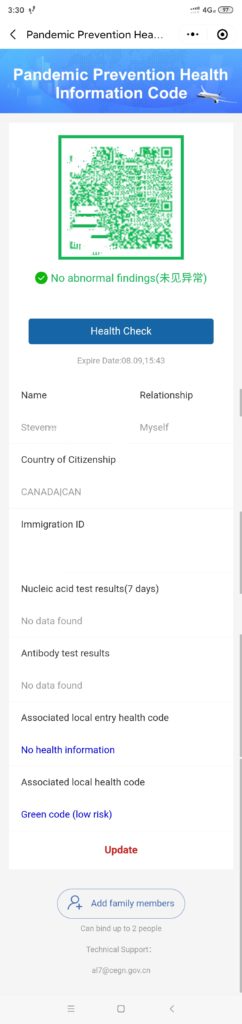

Other than tracking out whereabouts and travel history, each APP needs to give us the “Green Arrow” or “Green QR” code before we could enter any public space, be it a mall, subway, restaurants, or train stations. And that’s when the fun began.

How many total?

In total we needed to ensure we could get four green arrows: our Beijing health code, the national health code, the provincial health code, and our company health code. This is addition to ensuring we submit our health information every day by 12 pm to the company as part of current government requirements.

What do they need to know?

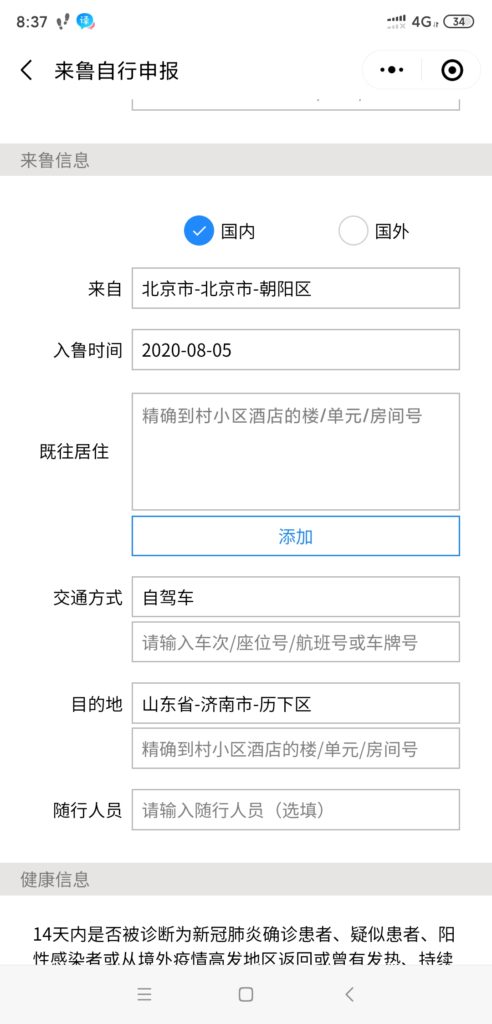

But each province has its own APP that we need to download, register for (with passport info photo and selfie with the passport), and then provide details where we’re staying.

The general information including your place of residence and where you’ve been for the last 14 days. If you’re arriving from abroad or have been in China the entire time. Which part of China do you live in and where are you going? They require you to declare if you’ve been to any “high risk” zones or if you’ve been in contact with anyone who was confirmed to have THE VIRUS. Finally, you need to present you temperature, which, currently, is being taken at every entrance around the country. Literally, any and every doorway has somebody standing by with a temperature gun ready to record your temperature, phone number, passport number, and name.

Why so many?

Simply put: to track the movement of people and any potential outbreak of THE VIRUS.

I’ve praised China’s efforts to quell the spread of the new Coronavirus and they continue to take serious, although sometimes inconvenient, measures to mitigate the chance of a second wave. In addition to masks, which are recommended but not necessary in most places, they ARE required when travelling on subways, trains, planes, or any other place where a lot of people congregate.

At first the APPs seemed daunting since the majority of them are written in Chinese. Once you get a few of the characters down (地址 di zhi “address”, 名字 ming zi “name”, 护照 hu zhao “pasport”) and the characters of your nationality (Canada is jianada 加拿大), you can usually make your way through them. Even without a lot of Chinese knowledge, modern technology has enabled us to take screenshots and translate the images. It works most of the time but sometimes the application will reboot so it pays to study the translation and then work your way through the sign up process.

But, it’s the times when WeChat or Alipay don’t apply that things can get tricky. Such as uploading passport photos (both of the information page and one of us holding the passport), or knowing the name of the hotel we’re staying at or its address. (The Hilton is 希尔顿 xi er dun in Chinese.)

And that was all well and good. I managed to get all four to go green before departing Beijing on my first work trip in seven months. Granted, there was very little by way of professional, medical check ups done to ensure the information I provided was correct. The APPs do state very clearly that if you have misrepresented any information then you are liable for punitive measures, among which would be a quarantine at your own expense.

How was the trip?

First or all, although we’re supposed to be “social distancing” (the latest politicized tool in the West), taking the subway in Beijing was, well, rather normal. It looks like we’re back to overcrowded subway trains during rush hour.

But once inside Beijing South train station, the crowds thinned out a little bit and I was surprised at how few people were there. It looked very similar to the number of people that were there during Spring Festival some seven months ago.

And then there was getting to Jinan itself.

The train was only about half full so there was lots of room to move around. I wonder if this is due to the 1 metre distance and so they only sold half the number of tickets or if there just weren’t enough people taking the train. In fact, there was no actual 1 metre distance since we were all sitting right beside each other in a group rather than one person occupying two seats.

Getting into Jinan City was a bit of experience only because once we entered the lobby area, we needed to scan the Jinan-specific QR code and then present the result to the security guard. I’m not sure what would happen if it the returned result wasn’t a green QR code.

After the train station and into the hotel, again, we had our temperature checked at the door, then, at check in, we needed to produce both the Jina-specific QR card and the National QR code, of which the clerk took pictures before scanning our passports.

After that, things were “normal” enough: temperature checks at entrance ways, hand sanitizer available everywhere, QR code scanning, but nothing too drastic. Oh, and plastic barriers between people during meetings.

On Friday, our work bus was boarded by some men clad in white hazmat-like suits and they requested to see our green QR codes and to take the temperature of everybody on board the bus. This is after some of us had been in the city for a week already.

Getting back to Beijing was a bit easier. The Jinan West train station had temperature scanners at the entrance way but I didn’t see any medical staff around. One Chinese guy was pulled from the ranks of travellers and told to sit in a demarcated area, which was just beside the line up of people entering the station. His temperature was too high so he probably had to take one of the tests as a result, but I’m not sure.

The train ride home wasn’t as busy as usual, nor were the stations. The subway was about half full but, in getting to the station in Beijing, it was packed, which was usual for Beijing rush hour. The 1-metre social distancing rule is tough to implement in a city of 30+ million people many of whom can’t afford private transport or, worse still, live so far outside of Beijing that it’s a better idea to take public transport into the city rather than drive on their own. At least you can sleep if you get a seat. Just remember to wake up in time.

And then once on the train and back to Beijing there was little by way of checking any of the QR codes. The only thing that you had to present to the public was the mask on your face. Other than that, we were left alone to our own devices, quite literally.