I had at least one moment of clarity in the past couple of months: Chinese sounded like a real language. That is to say, after returning to Beijing and spending some time away from the Chinese language, I was on the bus when the computerized voice announced the next stop. Without much thinking (although I was familiar with the bus route), I understood what the voice said. This, of course, threw me as I tried to parse the entire sentence for its meaning and failed, but I was able to catch the general gist of the message. Furthermore, I’ve noticed that when my Chinese colleagues speak to each other, it’s no longer a klangled, ching-changing, gnashing of the teeth. Instead, it’s a defined language with starts and stops and the ever so fine differentiation of consonantal sounds. That is to say, I can understand that they’re using words, not some secret code.

Let me clarify what I mean by “klanged, ching-changing, gnashing of the teeth.” First, Chinese is spoken from the from of the mouth, at the tip of your tongue and mostly at your front teeth with lots of help from your jaw bone. Other languages, such as English or Ukrainian (or Russian), are more guttural and come from the back of your throat. Chinese, however, has a series of consonants that sound extraordinarily similar to the untrained ear. For example, the consonants “j”, “zh”, “c”, “q” are all pronounced in a similar fashion as are “sh” and “x”.

Finally, the the vowels aren’t what they seem. For example, “qing” (please) isn’t pronounced “cheeng”, it’s pronounced “chee-yuh-ng”. This phenomenon, of course, is natural and obvious to native Chinese speakers, and they look at you as if you’re an alien when you say it wrong. That being said, there is perhaps only one teacher of mine (and none of my students) who pointed out that there are, in fact, three phonetic sounds in the Chinese “ing” (ee, yuh, ng).

The kicker is, however, that the pronunciation of Chinese can change depending on the tone of the word (there are four tones in Chinese) and, as I’ve found out, the dialect of the speaker. I am learning what’s known as the standard dialect of Mandarin, the Beijing dialect. The Beijing dialect is used in all official documents and most people can understand what I say. But when it comes to me understanding them, well, it’s a little bit more difficult. And my students? Well, most aren’t from Beijing so the way they say a word is different from the way that I’m learning it.

Speaking is still a love-hate experience. If I speak to my students they are apt to inform me what I really said based on the tones I used. Some of their translations are pretty funny, other times it’s just annoying. At this point, I’m not very concerned with what I really said so much as being understood given the context of what I’m saying. As I recall from my summer travels, given the context, the words I use are mostly correct and can be understood by most people. It’s almost as if my students become language purists when I speak Chinese and are hell-bent on revenge for the mistakes I pick out in their assignments. It’s amusing, but does nothing to encourage me to speak any more to them.

On the other hand, the manager at my gym complimented my Chinese saying that last year my language skills were “yi dian dian” (a very little). This year it’s “yi dian” (a little). So I responded, maybe next year my language skills will just be “yi” (a)… a joke that is more funny when spoken in person and done in Chinese. And most other Chinese people just give me a strange look when I try to repeat the joke. So I don’t repeat the joke much anymore. I only wrote it down for posterity. But believe me, it was funny at the time.

Reading is still difficult. One of my teachers insists I read Chinese characters even though there is zero-method to figure out the sound of a character. Yes, there is a way to recall the meaning of the character by way of parsing the individual parts of the whole, but there’s no way to figure out the sound itself. There are some books out there (Chineasy is the most recent and popular example) that explain Chinese characters by making little stories or drawings out of them while providing derivatives of that character. That’s all fine and good, but a story of a man (ren 人) doesn’t do me a whole lot of good when that man is then pushed up against another character, such as in the character for “gate” (men 们 ). As you can see, the two characters have vastly different pronunciations. I liken reading Chinese to a game of “Go Fish” in which you see a character and say a sound. If they match then you get to go again. But if they don’t match, then you sit in silence until your teacher tells you the answer.

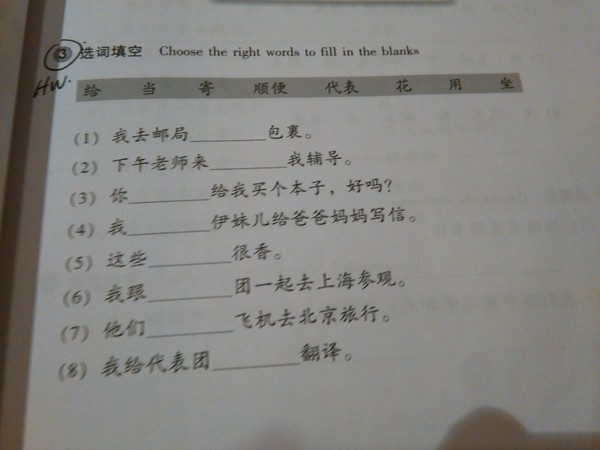

Finally, writing is getting much easier. There are three times I write Chinese. The first is either to answer questions or for practice in my textbook. My teachers’ views on my handwriting varies (I think) based on how tired they are of encouraging their students. Second, is on my cellphone dictionary. If I ever have a few minutes to kill I’ll typically pick out a few characters from around me and look up the words online by writing each character on my cell phone screen. It takes time but I’ve managed to figure out a few signs around the university as a result. And third, the culmination of Chinese ingenuity is in how their people use the QWERTY keyboard (the English layout of a keyboard) to write pinyin (the romanization of Chinese sounds) and then select the correct hanzi (the actual Chinese characters). So typing Chinese isn’t very difficult, though, again, if you don’t know the tone then you may not get the right character… and then people will laugh at you. And post a screenshot of your mistake on WeChat Moments so everyone else can laugh at your mistake.

Ah yes, WeChat. With the built-in dictionary that WeChat uses, I’m able to fool a lot of my students into believing that I can, in fact, read Chinese. If they only knew the truth.

All that being said and done, the good news is that Chinese is getting easier. I’m told my current level is about HSK 1.5, which suggests that I should be able to recognize or say about 100 characters or so (though the numbers 1-10 make up the first characters I know). Whatever the case, I’m mostly studying Chinese so that in 20 years I won’t regret not taking the opportunity to learn it. I’d love to end on a philosophical saying from China, but I don’t know any. And so it goes, learning Chinese.